Kentucky native and designer Hollis Maxson strives to be a storyteller through their art

- Gracie Moore

- Nov 17, 2024

- 4 min read

Updated: Nov 18, 2024

For Hollis Maxson, fashion isn’t just about making clothes. It’s a way to connect with people and be a storyteller, especially for the community in their hometown of Berea, Kentucky.

Maxson is a 21-year-old student at the Savannah College of Art and Design and a recipient of the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) Scholarship Fund in September 2024, receiving the CFDA x Crystal Bridges Heartland Scholar Award for their dedication and passion for the craft.

Photo provided by Jonathan Sage

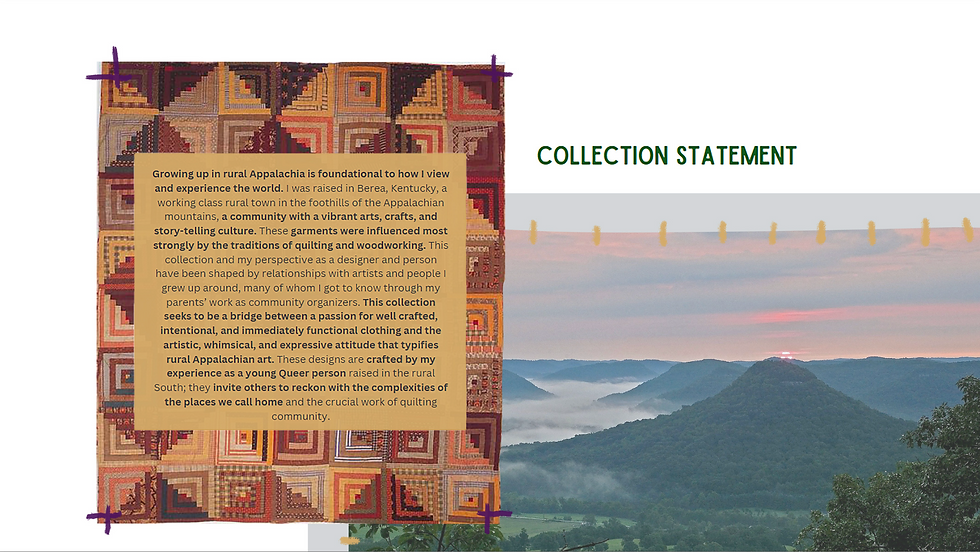

Maxson said they strive not only to create accessible, affordable and sustainable designs but also to create ones that will spark conversations about community. They tried to encompass all of this when making the award-winning collection which will grow into their senior thesis.

Art by Hollis Maxson, provided by Jonathan Sage

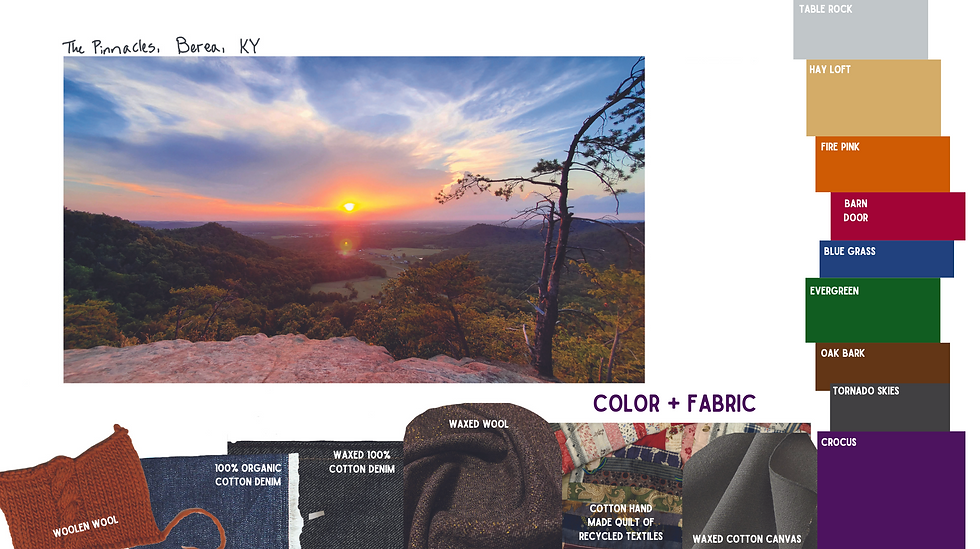

The 10-piece collection focused on how crafts like quilting and carpentry can build communities in rural areas, particularly Appalachia. Maxson said that they wanted the designs to be functional, durable and meaningful to the community they drew inspiration from.

Art by Hollis Maxson, provided by Jonathan Sage

“I think rural Appalachia particularly… those communities aren’t spoken about, or if they are, they’re painted with a really broad brush,” Maxson said. “I was really excited to just get into this idea of how do you actually make clothes that matter to people and matter to communities?”

Art by Hollis Maxson, provided by Jonathan Sage

Fashion is one of the most “universal conversations and art forms” to them, they said. They said that the ability to have so many different conversations with people through their art is one of many special things about fashion design.

“I think the thing that has always appealed to me… is being able to tell stories and to have conversations as a designer that are about people and that include people,” said Maxson.

One way that Maxson found they could create meaningful designs was by speaking to the people the designs are inspired by and including them in the conversation. They also wanted to ensure that the garments were functional while still looking nice.

Maxson ensured that they did adequate research on the crafts. They said that they spoke with many different craftspeople in Berea, asking questions about everything from pockets to zippers.

Art by Hollis Maxson, provided by Jonathan Sage

“I really wanted to make sure that every pocket had meaning and it was going to be useful. It wasn’t just let’s put a pocket here because it’s going to look good,” Maxson said. “It’s a pocket that people who do the work have said would be the most helpful, and this is a version that I think will fit with the artistic history and the garments. It’s blending this idea of workwear with this idea of storytelling from the crafts themselves.”

Both quilting and carpentry run in Maxson’s family, making this collection even more personal. Most of their uncles are carpenters or contractors. Their grandmother is a quilter and one of their muses for this collection and their art in general, they said. She taught them how to sew at a very young age. Maxson said that they even still have their great-grandmother's old Singer sewing machine that folds out of the table.

Maxson said “the idea of trying to make a difference in people’s lives” was something they saw often growing up in part because of their parent's work as community organizers. They said they were out with their parents from a very young age, seeing the work they did.

“My brother and I, there are pictures of us ages one to seven at all of these places with my parents, trying to get a sense of what it means to build authentic relationships with people. That version of authenticity and storytelling and building community… is really where I draw a lot of inspiration in the conversations I want to have,” Maxson said.

Art by Hollis Maxson, provided by Jonathan Sage

As Maxson continues to grow this collection for their senior thesis, they said they plan to highlight other art forms prevalent in Berea, like glass blowing or theatre. They said they want to continue highlighting Appalachia and the importance of generational knowledge on the arts community.

In this collection, Maxson said that they wanted to ensure that generational knowledge continues to be appreciated, saying that it’s “the heart of rural Kentucky and Appalachia.”

Art by Hollis Maxson, provided by Jonathan Sage

Having been taught how to sew by their grandmother and other family friends, they find themselves lucky to have had that knowledge shared with them. Through their work on this collection and in the future, they hope to continue to take generational knowledge and stories from communities to make their designs that much more impactful.

“Why do we want to hold onto generational knowledge? What are the parts that are important to keep moving forward and then what parts is it time for them to modernize?” Maxson said. “That’s part of this idea of being the next generation of Appalachian designers and being able to uplift these voices.”

stainless steel…

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理

U卡办理 U卡办理

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理

U卡办理 U卡办理

Stainless Steel…

蜘蛛池搭建 蜘蛛池搭建

stainless steel…

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理

U卡办理 U卡办理

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理

U卡办理 U卡办理

Stainless Steel…

蜘蛛池搭建 蜘蛛池搭建

stainless steel…

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理

U卡办理 U卡办理

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理

U卡办理 U卡办理

Stainless Steel…

蜘蛛池搭建 蜘蛛池搭建

stainless steel…

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理

U卡办理 U卡办理

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理

U卡办理 U卡办理

Stainless Steel…

蜘蛛池搭建 蜘蛛池搭建

stainless steel…

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理

U卡办理 U卡办理

万事达U卡办理 万事达U卡办理

VISA银联U卡办理 VISA银联U卡办理

U卡办理 U卡办理

Stainless Steel…

蜘蛛池搭建 蜘蛛池搭建